US federal research and development spending as a share of GDP has fallen by nearly two thirds since the mid-1960s — a trend accompanied by decades of low productivity growth. In a recent extended episode of Political Economy, Jonathan Gruber, Tony Mills, Margaret O’Mara, Bret Swanson, and I discussed how policymakers should reverse this trend and reclaim America’s place at the forefront of the technological frontier.

Jonathan Gruber is the Ford Professor of Economics at MIT and the co-author of “Jump-Starting America: How Breakthrough Science Can Revive Economic Growth and the American Dream.” Tony Mills is the director of the R Street Institute’s science policy program, which aims to equip policymakers with scientific expertise and to advance public policies that stimulate scientific innovation. Margaret O’Mara is the Howard & Frances Keller Endowed Professor of History at the University of Washington and the author of “The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America.” And Bret Swanson is a visiting fellow at AEI, where he focuses on the impact of technology on the US economy, telecommunications, and internet regulation.

Below is an abbreviated transcript of our conversation. You can read our full discussion here. You can also subscribe to my podcast on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher, or download the podcast on Ricochet.

Pethokoukis: Historically, what has been the American formula for

scientific and technological progress?

O’Mara: I think the short answer is the federal government threw a lot of money in technologists’ and scientists’ direction and got out of the way. It’s a real contrast to other industrialized nations. There was a massive surge of spending starting with the Manhattan Project and continuing in the Cold War. It was partially done directly inside the government via government research agencies, but it was also money that flowed from public coffers to universities, private companies such as massive defense contractors, and also to smaller companies like the pioneer Silicon Valley startups.

Swanson: You need both public and private support here. On the internet point, in particular, ARPA said we needed a new decentralized and packet-based communications idea, and they went out and hired private consultants to start building it. So there was a germ from the government, and it was a terrific idea. But it didn’t do a whole lot for several decades, right? It connected scientists and engineers, and it really did take the entrepreneurial, privatized explosion of the mid-’90s to then unleash the full forces. So it absolutely was both, but, like so many of these things, I want to emphasize that you absolutely do need entrepreneurial, decentralized efforts in order to fully realize the power of these ideas.

Mills: An important pivot point was the famous “Endless Frontier” report that Vannevar Bush, FDR’s science advisor, wrote, which laid the framework for a lot of postwar science policy. One of Bush’s key insights was recognizing that the large-scale, organized research efforts during the war were successful in part because of scientific discoveries, many of which were made before the war. So there were deep reservoirs of scientific knowledge that could be drawn on. You can see that in the development of radar, nuclear bombs, and even computing.

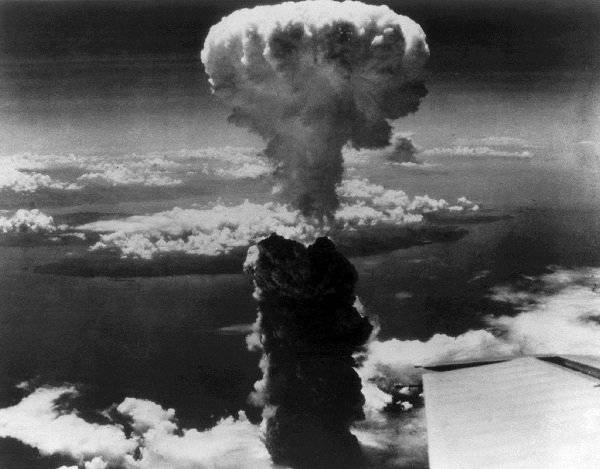

Smoke billows over the Japanese city of Nagasaki after an atomic bomb was dropped on the city August 9, 1945. Via REUTERS

Smoke billows over the Japanese city of Nagasaki after an atomic bomb was dropped on the city August 9, 1945. Via REUTERS

He wasn’t successful in his efforts to get science policy as he wanted it in every respect, but one of his key insights was the importance of support without control — giving the government a role in science policy, but to not control the direction of that research. It’s useful to distinguish between technological development and scientific research. It may be the case that in technological research, you have a particular goal, but a lot of the scientific breakthroughs that were key to innovation come from unexpected places, typically by researchers choosing their own directions.

Why has federal spending on science research not been a bigger priority? Why did we let it decline by two-thirds of GDP since the mid-1960s?

Gruber: There are three reasons. The first is that politicians and scientists stopped growing in the same direction. When there was a common goal in the form of defeating Hitler or going to the moon, they could get together and row in the same direction. But when they started disagreeing about things like Vietnam and the need for supersonic aircraft, politicians stopped respecting scientific opinion.

The second issue was the hubris of scientists, in the sense that scientists began downplaying some of the side-effects of their projects, like radiation poisoning and the damage done by pesticides. It made people realize that science wasn’t the universal good it had been pitched as.

Finally, there was budgetary pressure resulting from both the spending increases from the Vietnam War and Great Society programs and the anti-tax revolution in the 1980s. In a world where we have these mandatory spending programs like Social Security and

Medicare, the discretionary programs like R&D get shrunk.

O’Mara: I agree. Scientists went from being these trusted advisors, these people that Eisenhower called “my scientists,” to people that presidents from Nixon forward, of both parties, did not embrace as much. There was this real revolt against expertise, for good reason. Excesses of science and technology and techno-optimism — that proves not to be good for the population or the planet. And all of this is very expensive. Scientists were spending lots of money on things that don’t immediately have a commercial application, and it was very hard to build political momentum for it.

Why did we spend so much money before? It was the Cold War. War, turns out, is a very good reason for R&D spending. So another challenge for right now is understanding where R&D spending fits into many competing priorities in the absence of a similar geopolitical threat.

Pethokoukis: Jonathan, what is the short version of your plan to fix this decline in R&D spending? How much do you want to spend? Where do you want to spend it?

Gruber: This is a three-pronged plan. The first prong is the massive, historic (by recent standards) investment in R&D. The US currently spends about 0.6 percent of GDP on public R&D, leaving us 12th in the world. We would raise that by half a percent of GDP, moving us up to second or third in the world, depending on how you count things. That’s about a trillion dollars over 10 years. We estimate that kind of investment could create four million new jobs and go a long way towards bringing us back to more rapid growth.

The second prong of our three-pronged plan is to recognize that investors have had a strong bias towards a small set of coastal, superstar cities. As folks at Brookings have shown, 90 percent of all the new high tech jobs have arisen in about 10 cities across the US over the last 15 or 20 years. We need to spread that around our country. We denote 102 places that are highly educated, have excellent universities, and have a low cost of living, and therefore could be next-generation tech hubs. And while most of the money will be given to these places through typical mechanisms, a dedicated share of the funding will come from a public, non-partisan commission to decide where to throw some money to train tech hubs.

Equipment sits in the window of a lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S., November 21, 2018. Picture taken November 21, 2018. To match Exclusive USA-CHINA/STUDENTS REUTERS/Brian Snyder

Equipment sits in the window of a lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S., November 21, 2018. Picture taken November 21, 2018. To match Exclusive USA-CHINA/STUDENTS REUTERS/Brian Snyder

Finally, the third prong involves establishing mechanisms for ensuring the returns to these new innovations return to the public sector. For instance, if you can create new tech hubs, that’s going to raise the value of land a lot, so let’s capture the excess return to that land and redistribute that to people.

That, in a nutshell, is what we lay out. And the good news is that policymakers are listening to us and, indeed, there’s a similar bill out there right now called the Endless Frontiers Act — a bipartisan, bicameral bill. So there’s some interest in this.

Pethokoukis: Let me ask — first Bret, then Tony — how confident

are you all? Do you like this plan? Would you change this plan?

Swanson: I think the plan has potential. I want to be open to it, and I’m sympathetic to a lot of parts ofit. But I have some questions.

First, I’m not denying the benefits of clusters and agglomeration — people gathering and bouncing ideas off each other will continue to be important. However, there are a bunch of tools that we have now (the internet, cloud computing, simulations) that allow us to do powerful, decentralized research. It won’t work for everything —we’ll still need labs and so forth — but whether we need these physical hubs like we used to, I’m not sure.

Second, being from Indiana, I’ve certainly recognized the local economic development benefits, however, of seeing more places achieve what we’ve done on the coast. So I’m for that. But the last couple months — indeed, the last number of decades — could teach you the lesson that centralized bureaucracies maybe haven’t done the best thing.

Mills: I, too, am sympathetic to the proposal. But keep in mind: As valuable as R&D funding is, you also have to look at the underlying scientific discoveries and innovations that made things possible. You can give a lot of money to scientists that have some interesting ideas, but if there isn’t a broader infrastructure in which to transfer that knowledge to make it actionable and generate innovations, then it won’t amount to much. We need a broader ecosystem of discovery and invention — one that depends on science, as opposed to technology. I worry that the framing of our current policy debates neglecting this. And if we emphasize only the use-directed aspect of research, we’ll tend to only focus on the fashionable issues of the moment and miss out on possible innovations as a result.

Pethokoukis: What is the case for focusing all this money on existing institutions versus a prize- or award-style system for breakthroughs and innovations? What about doing that instead, or in addition?

Swanson: I think it’s an interesting question. I think we’ve had a lot of sclerosis across our research community and in institutions in general, so I don’t think it would be a bad idea to look for new sources and set up new institutions.

O’Mara: Yes, prizes and big, centerpiece initiatives can jumpstart things, everything from John Kennedy saying, “We will reach the moon by the end of this decade” to the DARPA prize for autonomous vehicles really advancing the state of the technology.

The autonomous ship “Sea Hunter”, developed by DARPA, is shown docked in Portland, Oregon after its christening ceremony, April 7, 2016. REUTERS/Steve Dipaola

But it’s also systemic. When I think of what we want a national science complex to accomplish, I think: What can public policy do? For it to accomplish what Jonathan’s proposing requires systemic change. It requires reevaluating and re-empowering science and government, and re-instituting things like the Office of Technology Assessment, which was a bipartisan entity advising Congress for two and a half decades on future tense matters — everything from acid rain to supercomputing.

Mills: This raises an important question: What is our current R&D system not doing well? Where are the current inefficiencies? We’ve talked about the geographic distribution problem, but there are lots of other problems. Scientists have to spend a lot of time on bureaucratic compliance. There are lots of worries about the peer review process. Entrenched institutions are absorbing a lot of the grants that come out of the government.

I think there’s a whole host of issues that we need to think through before we know how best to start funneling the money through the system, because if the system isn’t working well, putting a bunch of money into it may not be helpful on its own. We have to think about how this research money is being spent.