Online education needs three primary pieces of technology to work: the device at home, its connection to the internet and the computer program that delivers lessons and homework assignments from student to teacher and vice versa.

Arkansas school districts report deficits in all three areas, despite spending more than $150 million to prepare for online education during the covid-19 pandemic.

Schools abruptly shifted to distance learning when the pandemic forced them to shut down in March, highlighting the growing importance of technology in education.

It also forced Arkansas to confront inequities in students’ access to technology. The ability to learn from home is limited for students who have poor internet connections or computers, educators said, and the quality of their education can suffer.

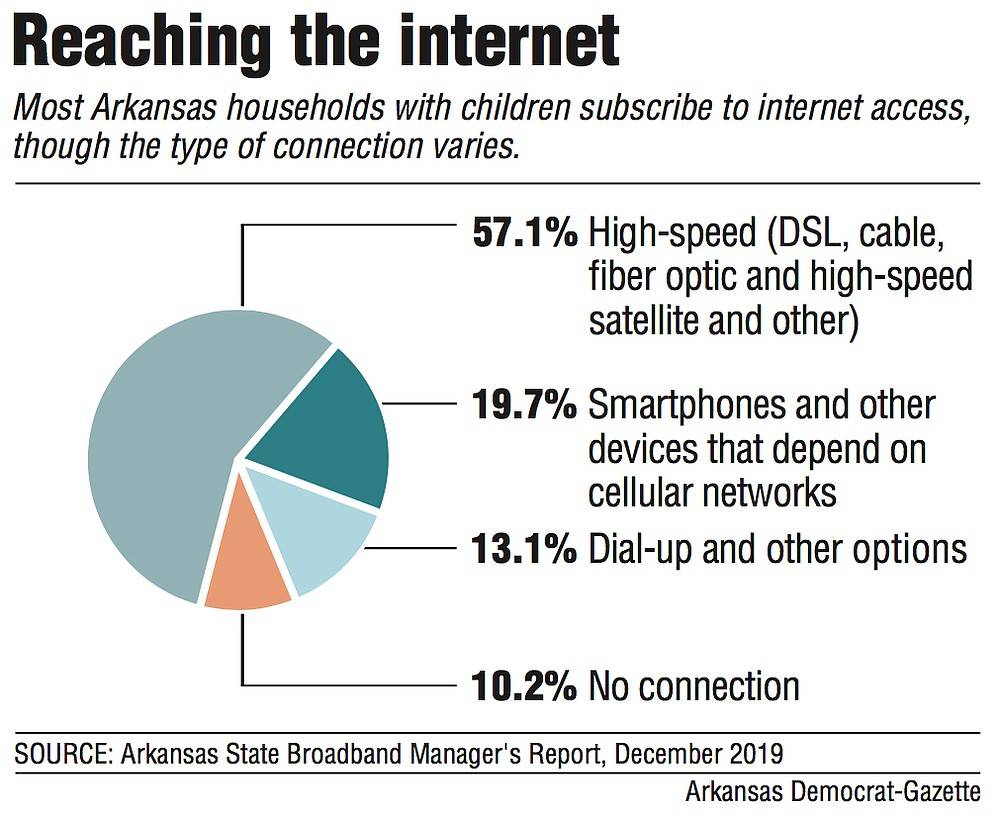

Some progress has been made since March on the technology front. Still, internet access remains an issue. One in 10 households with children have no internet connection, according to a 2019 Arkansas Department of Commerce report.

In an ongoing survey by the Arkansas Department of Education, 178, or 68.7% of the state’s 263 school districts in the past few months reported some students with no internet access at home.

The department directed school districts to prepare an education program for this school year that relies on in-person and online instruction with the flexibility to blend them and pivot from one to the other.

Most of the state’s estimated 480,000 public school students are learning in-person with their teachers, though a significant number opted to remain at home and get their educations online. The Education Department’s survey showed 236 of 263 districts reported at least 5% of their students had chosen some online learning for this fall.

The online students will be expected to learn as much and at the same pace as their peers sitting in classrooms.

The Commerce Department report found that most residential internet access uses cable or other high-speed options. And many districts had Chromebooks or other portable computers on hand for most or all students to take home.

Still, challenges remain.

Around one-sixth of those with connections have only wireless access — essentially the network connection smartphones use, according to the Commerce Department report. Computers typically can’t access the internet using a wireless connection without a special device.

Successful online learning also requires parent involvement, district support of parents and a commitment to improving online delivery, educators said.

Parents and district officials noted some problems in the first few weeks of school this fall because of poor connections to laptops and promised Wi-Fi devices that hadn’t arrived.

The state has authorized giving at least $125 million, mostly in federal money, to towns and districts to acquire or improve broadband. Districts also reported spending at least $22 million in federal funding that they received earlier this summer on technology.

The Wynne School District in east Arkansas, with an enrollment of about 2,600 students, received $600,000 in Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act money. Superintendent Carl Easley said about one-third of that went toward 1,020 Chromebooks. The district now has enough to provide one for each student.

Those machines arrived Aug. 27, nearly three months after the district ordered them.

About 30% of the district’s students were doing distance learning as of the second week of school, though Easley estimated that only about 40% have internet access at home.

“There’s been some glitches,” he said. “There’s a lot of connectivity problems for some who went virtual, and we’re lacking Wi-Fi in a lot of parts of the county.”

The district in August installed public Wi-Fi spots in eight locations in addition to Wi-Fi spots on each school’s campus, he said.

MAKING A CONNECTION

Candace Williams is a single mother who lives in rural Phillips County in east Arkansas. Her only child, Caleb, is a third grader in the Marvell-Elaine School District.

The 8-year-old is receiving his education online this school year in part because of his mother’s concerns about covid-19.

They have satellite internet service at their home, but it is slow and expensive, Williams said. The service has cost Williams upward of $300 per month since the pandemic hit.

“I have the highest data plan. They say that I run over that all the time, so I have to pay more to get more data,” she said.

Williams contemplated taking Caleb to the nearest McDonald’s parking lot, 45 minutes away, to use the restaurant’s Wi-Fi, or taking him to her office in Little Rock, a full two hours away, she said.

One week after school started, he received a hot spot from his school, free of charge. He can stream a video much faster now.

Williams is executive director of the Rural Community Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy group for rural Arkansans. She is thankful for the Arkansas Rural Connect program, which Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced last year as his way of delivering high-speed broadband service to rural communities.

The Rural Connect program had distributed a total of $26.2 million for 19 communities as of Sept. 3 to expand broadband access, according to the Commerce Department. The program received $25 million from the state and the federal CARES Act. The CARES Act Steering Committee and the Arkansas Legislature in August approved an additional $100 million for the program.

Hutchinson announced in July that the state would spend $10 million in federal aid to buy about 20,000 Wi-Fi access devices for families with school-age children, so those kids can have home internet access. The devices will be provided to families based on need and come with 24 months of unlimited data, Hutchinson said.

Williams feels not enough was done soon enough to prepare for this year’s high demand for online education. Many parents sent their children to school this fall because they didn’t get hot spots in time or didn’t have broadband service at home, she said.

TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENTS

Money is flowing around the state to shore up the online learning system.

Bentonville reported to the Education Department that it spent $860,000 on Chromebooks; North Little Rock chipped in more than $500,000 for Chromebooks, temperature scanners and nurse laptops.

The governor in July announced a $10 million deal with several wireless providers to use CARES Act money to buy 20,000 Wi-Fi access points, essentially antennas to connect computers to the wireless cellphone network.

The state distributed Wi-Fi devices based on enrollment rather than percentage of households with no internet to try to be fair to all schools, said Don Benton, assistant commissioner at the Education Department’s Division of Elementary and Secondary Education.

“We recognize that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to continuity of learning for students amid this pandemic, but everyone is learning innovative ways to make it happen with the resources at hand,” Benton wrote in an email.

Forty-eight districts reported in the Education Department survey that they didn’t have the technology devices needed to begin school the week of Aug. 23. Many of the devices will arrive sometime this month, administrators said.

“It’s really slow going for getting any type of technology right now” because everyone’s buying the same things at once, said Barbara Warren, superintendent of Pine Bluff and Dollarway schools.

Pine Bluff in recent weeks reported more than two-thirds of its students are staying home for school, but more than 40% also have no home internet. The district will receive 115 portable Wi-Fi access points and buy roughly 400 more, Warren said. The district reported spending more than $250,000 from federal assistance on technology.

In the meantime, schools and other community buildings within the district are broadcasting Wi-Fi signals to use outside, and the district is looking into placing Wi-Fi-equipped buses around town, as it did in the spring.

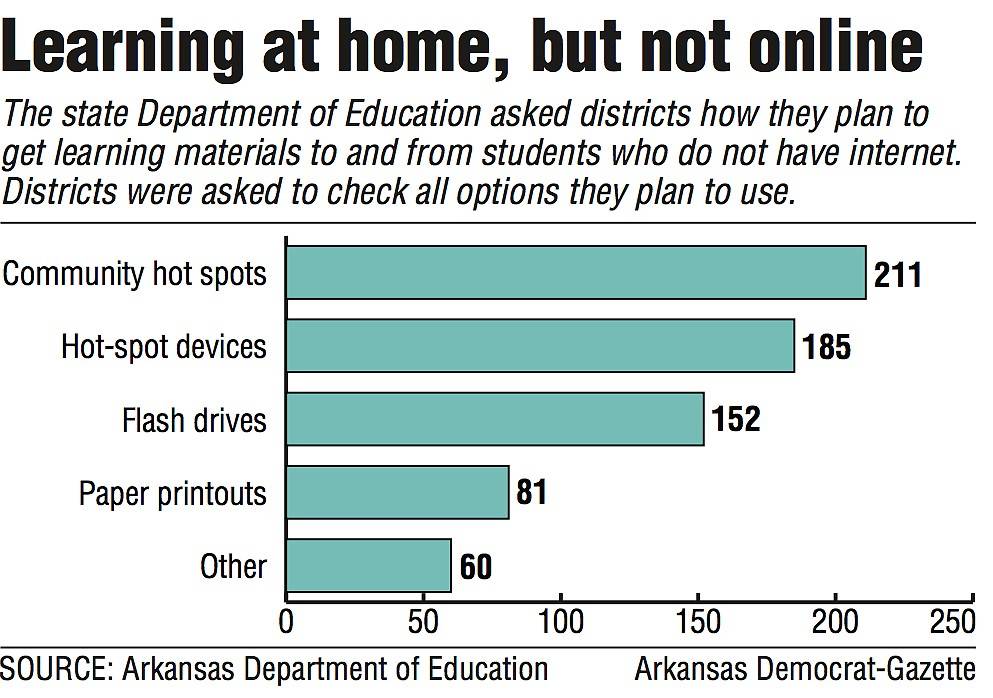

Fort Smith, Mountain Home and other districts also have set up community networks where students can at least swing by for a moment to download assignments. Jackson County, Mena and dozens of other school districts told the state that they’ll resort to paper packets for schoolwork for those students who simply cannot access the internet.

“I think we have the ability to connect all of our students before it’s over,” Warren said.

Thirty-seven school districts reported to the Education Department that they had spent more than 40% of the federal pandemic funds on technology.

The districts vary in size from the state’s largest in the 2019-20 school year, Springdale, to the Strong-Huttig School District in Union County, ranked 247 last year out of the state’s 263 districts.

Twenty of those 37 districts had fewer than the state average of 32% minority enrollment. Figures for poverty, as measured by participation in the federal free and reduced-price lunch program, showed 27 of the 37 districts had rates higher than the state average of 66%.

In the survey, districts reported their spending in categories ranging from none to $50,000 to more than $500,000.

Using the midpoint in each category divided by 2019-20 enrollment, spending per student ranged from $480 in Lead Hill in Boone County to $48 in the Mayflower district. Two districts, Springdale and Wynne, simply reported spending more than $500,000 with no top range available.

PARENTS’ PERSPECTIVES

Brittaney Bowman, whose first grader attends Friendship Aspire Academy’s public charter school in Pine Bluff, makes sure her daughter’s computer is the only device connected to her home internet during school hours; otherwise, the connection is too slow for video meetings with teachers and classmates.

Her service provider told her the tower providing her wireless signal is too far away to be stronger, so Bowman is looking to switch providers.

Other parents of online students said their connections are working fine, with some expected hiccups.

“The first day of virtual, of course, it was a wreck,” said Samantha Savage, whose sixth-grade twins are online and her 16-year-old attends high school in person in the Watson Chapel School District, which covers part of Pine Bluff. “The sound was going out. The screen was glitching. A lot of kids were speaking at once.”

Teachers have improved their muting skills, and they and the district’s technical support for the Chromebooks have been quick and easy to reach, Savage said.

In the ongoing Education Department survey of school districts, just more that 32% of districts reported offering parents and students training in the online learning programs that the districts use, and about 30% reported offering parents and students training in blended learning techniques.

Lucas Regnier of Fayetteville and his wife are both attorneys working from home because of the pandemic. They have four children. Each child is enrolled in the Fayetteville School District and doing online education to some extent.

The fourth grader is full-time online. The seventh and 10th graders are doing online three days a week and going to school twice a week. The 12th grader is going to school four days a week, with one day per week online.

Regnier helps manage the kids’ education, especially for the youngest one. The first week of school was “sheer chaos,” but since then, the children and parents have settled into a good routine, Regnier said.

He noted a financial impact on the family because he’s able to devote only about half of the time he normally would to his law practice. Online students, especially those of elementary age, need an adult present to supervise them, he said.

“You can’t just cut them loose and catch up with them six hours later,” he said.

Jessica Rogers of Cabot has four children. She’s home-schooling the younger two, a first-grader and a fourth grader. She enrolled the older two — a sixth grader and a seventh grader — in Arkansas Virtual Academy, an online charter school.

Normally, all four children would be attending Cabot Public Schools, but Rogers and her husband kept them home because some family members have health conditions that put them at greater risk of illness during the pandemic, she said.

Arkansas Virtual Academy’s first day of school was riddled with technical issues, Rogers said.

“It’s certainly improved over the last several days,” she said at the end of the first week. “But it’s been all-consuming.”

She said she’s home-schooling her younger two children because managing the demands of online school for all four kids wasn’t feasible.

“I have to log in on my own account and continuously make sure they are doing the right assignment at the right time,” Rogers said. “I have to really know what I’m doing. I feel sorry for parents who aren’t tech savvy, because it would be an impossible feat for them.”

Some families have had to learn how to navigate the computer platforms and the programs where lessons arrive and completed activities are sent to teachers. Fort Smith and others have held online open houses and video classes to help.

Cathy Adams of Fort Smith and her husband are in their 70s and raising their school-age grandchildren, she said. It’s been a steep learning curve to work with the computers, but every person she’s reached out to for help has been kind and generous with their time.

“And I don’t know where they’re getting it,” Adams added with a laugh, referring to that patience and time. “I am aware of the effort that they make and what they have done in such a short amount of time.”

The expanded online capacity for education seems likely to outlast the pandemic, perhaps for inclement-weather days that would otherwise be days off, several administrators said. As long as students have electricity, they can have learning, Warren said.

“I don’t think we’re ever going to go back to exactly what things were like before,” Fort Smith Superintendent Doug Brubaker said. “A lot of this is here to stay.”

Where the broadband grants went

The Arkansas Rural Connect program has made 23 awards to service providers and local governments totaling $28,248,077 to expand broadband access. The program has an overall budget of $124 million for grants, where $119.3 million is available from federal funding and $4.7 million is available from state funds.

GRANT RECIPIENTS

Arkansas Telephone Co. and Fairfield Bay – $1,568,750

Pinnacle Communications and Ozark – $1,909,264

CableSouth Media 3 and Lonoke – $2 million

Premier Holdings & Nashville – $448,580.30

Hillbilly Wireless and Cave City – $803,762

Magazine Telephone Co. and Magazine – $1.03 million

Hillbilly Wireless and Cotton Plant – $497,001

CableSouth Media 3 and Hamburg – $2 million

Comcast and Earle – $1.8 million

Aristotle Unified Communications and Hazen – $1.9 million

Central Arkansas Telephone Co. and Donaldson – $1.2 million

CableSouth Media 3 and Crossett – $2 million

CableSouth Media 3 and Carlisle – $2 million

East Arkansas Video and Palestine – $927,000

Hope Community TV and Emmet – $193,000

Premier Holdings and Center Point – $714,495

Resort TV Cable Co. and Diamondhead – $601,000

Aristotle Unified Communications and Saline County – $3 million

Windstream and Montgomery County – $1.6 million

SkyFiNet and Jackson County – $498,873

Windstream and White County – $2.5 million

Premier Holdings and Hempstead County – $1.1 million

CableSouth Media 3 and Humnoke – $2 million

About ‘Covid Classroom’

“Covid Classroom” is an ongoing series examining the effects of the corona-virus pandemic on kindergarten-through-12th-grade public education across Arkansas. The project is reported and presented by the news staffs of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, with the support of the Walton Family Foundation.

The series is produced independently, with no input in the research, writing or editing from the funding organization.

All elements of the project will be available online for nonsubscribers.

“Covid Classroom” is one of several similar projects around the country involving 16 news organizations and 50 newsrooms.

Melinda Bunyard, a teacher in the Virtual Innovation Academy, shows her workspace and digital classroom software Thursday at the academy’s wing in the Don Tyson School of Innovation in Springdale. The school is part of the Springdale School District and provides virtual learning for the district.

(NWA Democrat-Gazette/Andy Shupe)

A sign advertises public Wi-Fi at the Pine Bluff Public Library, one of several public internet networks in place around the state to help online students who don’t have internet connections at home.

(NWA Democrat-Gazette/Dan Holtmeyer)

Reaching the internet

Learning at home, but not online

Getting connected